Marrickville Anzac Memorial Club

When Australia leapt into the European war in 1914 Marrickville was in the thick of it.

The military had recently purchased land on Addison Road (currently the Community Centre) and would eventually establish military headquarters with a recruitment centre and training ground. Thomas Holt’s mansion and estate, the ‘Warren’, was commandeered as a military centre and billet for the 7th Field Regiment.

Image: Australian War Museum.

Marrickville Council, led by Mayor John Ness, a staunch imperialist and war supporter, rallied to the Empire’s call. On Friday 12 November 1915, the ‘Coo-ee’ marchers (who left Gilgandra with 25 and arrived in Sydney with 263 recruits) were given “a rousing reception” as they marched down Marrickville Road from Dulwich Hill and then up Victoria Road to Newtown.

Along the Marrickville-road…the men had a rousing reception…At the Marrickville Fire Station, the fire men marched out in full uniform, and saluted the men. Further along the women of Marrickville distributed gifts and flags. In Silver-street from the balcony of Mr. Bidway’s house the Mayor welcomed the men on behalf of the people of Marrickville.

Gilgandra Weekly, With the “Coo-ees”, Page 3, 19/11/1915.

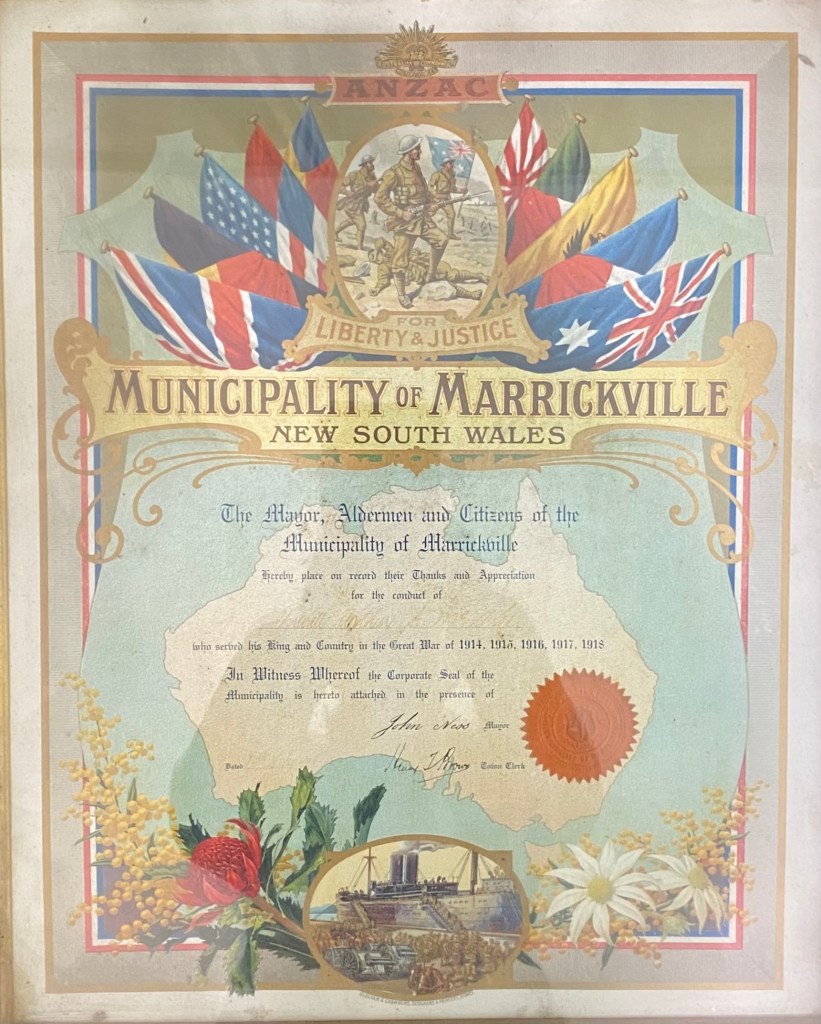

About 4,000 Marrickville men (the municipality being Marrickville, Dulwich Hill, and parts of Sydenham, Enmore and Petersham) enlisted and also marched off to war. Unfortunately, I cannot find a record of the number of Marrickville women who enlisted and died during the war.

Coming home

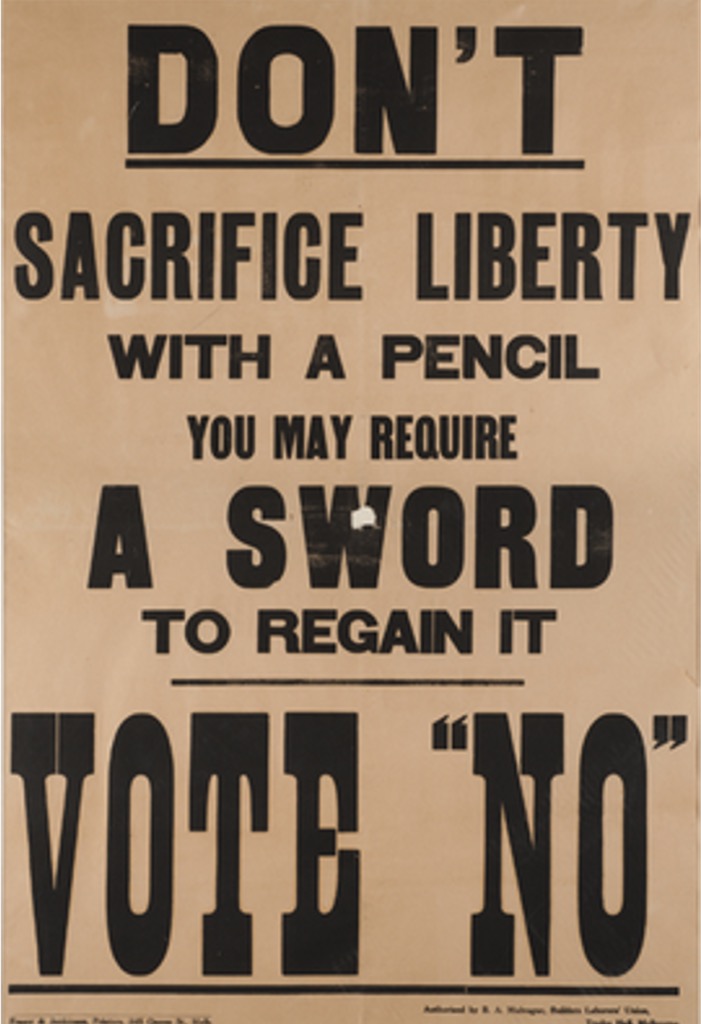

But with the war dragging on, the death toll climbing and the physically and mentally damaged returning home to their families, people lost their enthusiasm. In the first referendum on conscription the people spoke and, according to a Sydney Morning Herald report of 31 October 1916, Marrickville said ‘No’ by a majority of 1,361 votes. The ‘No’ majority for Petersham, St. Peters and Tempe was greater at a combined 2,357.

When the war was over, about 460 Marrickville men did not return home. Many of those who did carried a new disease (known as Spanish ‘flu), wounds and scars, what is known today as PTSD, and a type of alienation from society that years of war can give you.

Marrickville Council had erected a monument to the dead and issued certificates of appreciation to the soldiers and their families. Returnees marched at the head of the parade at the opening of the new town hall. Along with the cenotaph, the new town hall also had a captured German gun on the forecourt.

Poster: Inner West Council Library & History Services

Feted and lionised, when all the jubilation was over they were expected to settle back into society, to normality. The Government helped with housing assistance, pensions, medical treatment and jobs.

Non-government organisations, such as the RSL (it’s most recent name), were established to advocate on behalf of veterans. But the ‘official’ RSL was not necessarily what the average digger was after. It was bureaucratic and perceived as officer-led.

Who could possibly understand the horrors, the humour and the camaraderie of the ordinary enlisted soldiers as described by Joe Maxwell in his war biography ‘Hells Bells and Mademoiselles”?

The working-class soldiers of Marrickville were looking for something more. Ironically, it was a leading businessman and veteran, officer Lieut. H.T. Seymour, who provided a solution and the impetus to get it initiated.

Harry Seymour was a local builder and building supplier, who had created the largest suburban store in NSW on the corner of Marrickville and Victoria roads, known locally as Seymour’s Corner. With these business commitments he still decided to enlist in 1917 at the age of 44. He had served in France as a lieutenant in the 17th Battalion and returned home safely, then led the local sub-branch of the RSL.

Seymour, along with many others, thought more needed to be done. His focus was on the bond that had developed between men of diverse backgrounds and whether it could endure in civilian life.

The often-told origin story of what would become the Marrickville Anzac Memorial Club (MAMC) was this:

Harry Seymour was moving down from the front to a rest area before going on leave. After walking about 15 kilometres in full marching order and covered in mud he was just about “all in”. It was then that he met a young soldier who insisted that he carry Seymour’s gear for the rest of the journey.

He had seen so much of this happen and the thought crossed his mind: “I wonder if this spirit will always continue when we get home?”

(From MAMC Golden Anniversary Booklet)

Harry was determined that it would and a club would be the way to do this.

The club proposal received immediate support from council and local NSW parliament representative Carlo Lazzarini. A Labor MP and anti-conscriptionist, Carlo with his wife Myra, were much-loved members of the community and strong MAMC supporters throughout their lives.

Events were organised hoping to raise 6,000 pounds. Seventy percent would be used to build a memorial hall and 30 percent would be used to establish a bursary for the education of children of veterans killed in the war. The Defence Department recorded 3,220 such children in NSW in 1919.

Image: Marrickville 75 Years of Progress 1861-1936.

Land was eventually purchased in Garners Avenue and under the supervision of Harry Seymour a club house was built. When completed, it contained a hall with dance floor, a reading room, a billiard room, an office, and was surrounded by two large verandahs.

The first first

During this process the Marrickville sub-branch of the RSL, not happy with the decisions of that organisation, allowed their membership to lapse. The sub-branch took the name Marrickville Anzac Memorial Club and 53 people signed up.

This decision had significant implications as other sub-branches followed suit. These branches got together and formed their own organisation known as the Australian Legion of Ex-Service Clubs. The members of the club took some pride in this, as can be seen on the beer coaster below.

Photo: Rod Aanensen

The official opening of the new club took place on 30 July 1921, with the NSW Governor Sir Walter Davidson and an estimated 2,000 spectators attending.

There was a triumphal procession to Garners Avenue with the Governor and Dame Margaret Davidson, the mayor and councillors, and the club executive. They were escorted by a guard of honour made up of returned servicemen and boy scouts.

In a show of strong community support, it was reported that almost every house in the municipality flew flags for the occasion.

Mont Saint-Quentin, France and R.T. Williams won the Military Medal at Joncourt, France.

Image: Golden Jubilee of Marrickville Anzac Memorial Club 1921-1971

But the first few years were tough; they had the building debt and little money. The membership was not growing as they had hoped. Yet public support remained strong and a public meeting called by the mayor saw the establishment of the Auxiliary Committee to help raise funds to get rid of the outstanding debt.

The committee decided to run a ‘Queen of Marrickville’ competition. This proved very popular and a large sum was raised, possibly due to the fact that Matron Alice Cashin, Royal Red Cross Medal and Bar – MAMC member and ‘Digger’s Representative’ – was in the running. Matron won by a country mile. The competition continued for many years; the debt was erased and crisis averted.

The patron of the Auxiliary Committee was Sir William Vicars (Vicars Woollen Mills). He was so impressed with the club he wrote a cheque for 300 pounds so they could buy land next door to create a tennis court. Tennis was becoming extremely popular at this time and the courts were a great asset.

In a club of highly decorated individuals these two stood out. Lieutenant Joseph Maxwell, Victoria Cross, Military Cross and Bar, Distinguished Conduct Medal. Matron Alice Cashin, Gold Royal Red Cross and Bar, twice mentioned in despatches. Both settled in Marrickville after the war. Photo: Maxwell, Australian War Memorial. Cashin,unknown

The finances of the club were then maintained by the ‘Ladies’ Auxiliary’, whose membership for many years never exceeded 12 women. Before the club acquired a poker machine licence in 1954, the women earned the bulk of the club’s funds via raffles, dances and housie afternoons. In the period from 1944 to 1954 they averaged 2000 pounds per year. The men of the club were quick to acknowledge this vital contribution; after all, it kept the club afloat.

The second first

In 1927 MAMC was involved in the creation of the Dawn Service in Sydney as we know it today. At this time, commemorations on Anzac Day took place during the day or the evening. Marrickville Council conducted its first in 1916 but it was held at midday. The origin of the Dawn Service was passed down in the lore of the club.

A group of five members of the Ex-Service Clubs were wending their way home in the early hours of the morning of 25 April. One was Jim Davidson of MAMC. As they passed Martin Place, they noticed an elderly woman bending before the war memorial to place a bunch of flowers at its base.

One of the men, George Patterson (Epping), asked the woman if they could help. They could not, but they bowed their heads and said a prayer. They then went on their way. However, that powerful moment remained with them and at the next meeting of their association a motion was passed to lay “a wreath on the Cenotaph at dawn 4.30 a.m. on 25th April 1928”.

On the day, about 130 people were present and stood at the cenotaph, laid a wreath and said a prayer. The following year, the Returned Army Nurses’ Association was represented and 250 people joined the service when a prayer was said and ‘Reveille’ sounded. From this simple ceremony, today’s major event has grown. Until 2009, in recognition of the role played by MAMC, members were at the head of the right-hand column of marchers that headed down Martin Place to the Cenotaph.

Photo: Sydney Mail,’The Marching Feet of Anzacs’,Page 26, 29/4/1936

Change

The club had always just been for ex-service men. A large influx of new members joined after WW2; so many that membership was restricted for a while. But like-minded ‘associates‘ had also been allowed to join them. As the years moved on and members grew older, the number of associates increased.

However, finances were always an issue. Could the club remain relevant to younger people and to the new members of the Marrickville community for whom Anzac had less significance?

Then in the early hours of 19 November 1979, during renovations, disaster struck. A fire tore through the club and destroyed 90 percent of the buildings. It was attributed to old and faulty wiring in the ceiling. Miraculously, the office with all the club’s records was saved.

The club spirit was still strong and a temporary building, jokingly named ‘The Woolshed’, was up and running by December. This remained the club until new premises were built and officially opened on 4 November 1981. The opening was conducted by the Governor of NSW Sir Roden Cutler, just as the last had been opened by Sir Walter Davidson.

Image: Rod Aanensen

The end

With the new premises containing a bistro, restaurant, poker machines, hairdresser and dance hall, the club was able to continue financially, but it struggled. By the late 1980s it was again in financial trouble and remained so in the following years due to poker machine taxes and indoor smoking bans.

Finally, in 2007 the club, which still had 1350 financial members, went into voluntary administration with debts of $2.7 million. There was some hope for the membership when a businessman offered to buy the premises for $2.4 million but the bank rejected the offer. The club was wound up in 2008, and in March 2009 the club site was sold to a developer. It seems that at the same time all the club’s contents, fixtures, fittings and, most importantly, memorabilia were sold through an online auction house.

And so it was gone.

A ‘statement of significance’ for the club was provided to the council as part of the Development Application process. It didn’t see any significance in the buildings as they were, but did recommend that:

“…on the frontage to Garners Avenue below the mail boxes of the terraces 8 to 14 the following memorial plaque be displayed

“Former Marrickville Anzac Memorial Club”

“The interpretation memorial plaque will provide a daily reinforcement of the site’s significance to the returned service people.”

Lest we forget.

Rod Aanensen

‘The Chipilly Six, Unsung Heroes of the Great War’ by Lucas Jordan tells the stories of six soldiers who managed to do the impossible at Chipilly Spur on the Somme River in 1918. It also tells the story of the Marrickville Anzac Memorial Club as two of those six became members: Quartermaster Sergeant Jack Hayes DCM and Private Albert ‘Jerry’ Fuller MM.

I recommend you read the book. Thank you.